Happy 200th birthday, Florence Nightingale

She would have a lot to say about how to deal with the coronavirus.

Florence Nightingale was born on May 12, 1820 into a wealthy family, and grew up fond of mathematics and statistics. To her parents’ chagrin, at age 17 she decided to become a nurse, and in 1854, after lobbying friends and uncles in Parliament, led a team of nurses to Scutari, a hospital on the Bosphorus that treated the wounded from the Crimean war. This was 20 years before Pasteur and Koch developed germ theory and a hundred years before antibiotics; it was years after Ignaz Semmelweis figured out that we should wash our hands, but everyone ignored him or thought he was nuts. However, she was involved in the Sanitarian movement, and according to Christopher Gill, “believed that, by keeping patients well-fed, warm, comfortable, and above all clean, nursing could solve many problems that 19th-century medicine could not.”

Soldiers who got to Scutari came with injuries from battle, but they died from typhus, typhoid, cholera, scurvy, and dysentery. Nightingale and her team found them packed together on filthy canvas sheets.

Her interventions, considered at the time to be revolutionary, seem in hindsight to be acts of common sense. She and her nurses washed and bathed the soldiers, laundered their linens, gave them clean beds to lie in, and fed them, while working and lobbying to improve the overall hygiene of the wards. She helped establish a rational system for receiving and triaging the injured soldiers. As the wounded soldiers disembarked, they were stripped of their blood- and offal-soaked uniforms, and their wounds were bathed. To prevent cross-contamination between soldiers, Nightingale insisted that a fresh, clean cloth be used for each soldier, rather than the same cloth for multiple patients. She set up huge boilers to destroy lice and found honest washerwomen who would not steal the linens. She shamed hospital orderlies into removing buckets of human waste, to clean up the raw sewage that polluted the wards, and to unplug latrine pipes. At her behest, new windows capable of opening were installed to air out the wards.

And this sounds familiar:

In response to rampant petty corruption that was siphoning off medical supplies, she established a parallel supply system for critical materials and food, and she proved that the official supplies were being stolen by sending her representatives into the Turkish markets to buy back the purloined goods.

She cleaned the place up, in terms of both health and management; it was one thing to have the floors scrubbed and the sheets changed, it was another to deal with the British officers in charge. She wrote:

The three things which all but destroyed the army in Crimea were ignorance, incapacity, and useless rules; and the same thing will happen again, unless future regulations are framed more intelligently, and administered by better informed and more capable officers.

Army bureaucrats did everything they could to demean or ignore her work; much like what doctors said about Semmelweis, “the army surgeons resented the power she wielded and the implication that they were somehow culpable in the deaths of their patients.” When they saw the death rates drop dramatically, they tried to take credit for it. As Christopher and Gillian Gill note in Nightingale in Scutari: Her Legacy Reexamined, in words that sound familiar today:

Duncan Menzies, the Chief Medical Officer at Barracks Hospital in 1854, did his best to thwart Miss Nightingale, owing to the fact that her documentation of the supply shortages in Scutari flatly contradicted his own reports that the army “had everything – nothing was wanted.”

According to the Gills, Nightingale’s influence and legacies include:

Infection control

Many of our current health care practices, such as isolation of patients with antibiotic-resistant pathogens, avoidance of cross-contamination, routine cleansing of all patient areas, aseptic preparation of foods, ventilation of wards, and disposal of human and medical wastes, trace their origins to practices enacted by Nightingale at Scutari.

Epidemiology

Florence Nightingale’s Coxcomb diagram from her 1857 report to Parliament about the Crimean War/Public Domain

Florence Nightingale’s Coxcomb diagram from her 1857 report to Parliament about the Crimean War/Public DomainThis may be even more important when looking at circumstances surrounding COVID-19, when an understanding of the numbers is so critical. She wrote:

“All Sciences of Observations depend upon Statistical methods—without these, are blind empiricism. Make your facts comparable before deducing causes. In complete, pell-mell observations arranged so as to support theory; insufficient number of observations; this is what one sees.” The mortality diagrams that she invented for her report about the Crimean War remain models of elegance today. One of her most famous achievements was to prove that the majority of soldiers in the Crimean War died not of war wounds but of fever, cholera, diarrhea, dysentery, and scurvy, all of which are preventable conditions.

Meanwhile, in 2020, the biggest issues we face in dealing with COVID19 are washing of hands, sterilizing surfaces, keeping our distance, separation and isolation, testing and counting and analyzing the numbers. Florence Nightingale didn’t know about germs (she was a firm believer in the Miasma theory, where disease was carried by smelly air), but she did understand contagion.

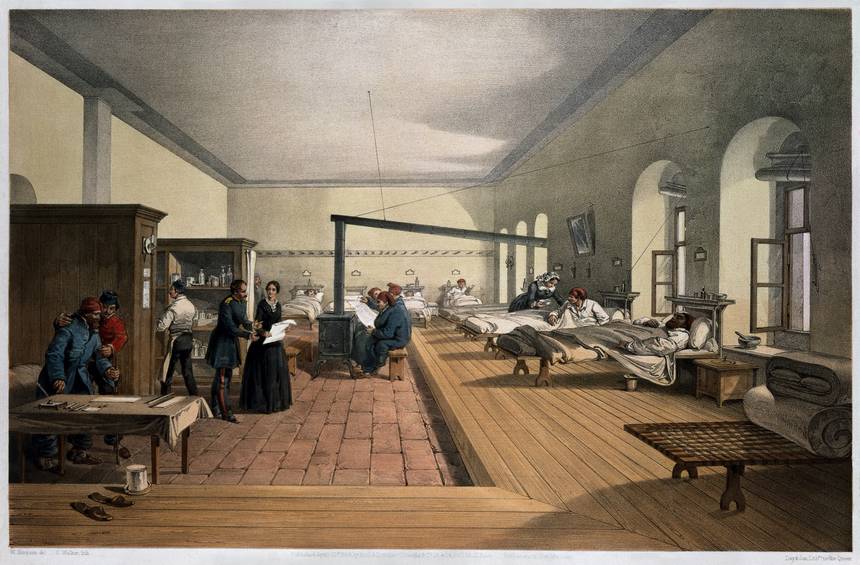

Florence Nightingale in Crimea/Public Domain

Florence Nightingale in Crimea/Public DomainWriting in the Guardian, Carola Hoyos asks the question directly: How would Florence Nightingale have tackled Covid-19?

Nightingale came back from Scutari a celebrity. Today, she would have millions of Twitter followers and use her popularity to press and cajole the government to make informed decisions about when to come out of lockdown and how to decrease the enormous death toll in care homes. And also to fundraise for supplies, as she did in her day.

I am not sure about Twitter, but so many of the parallels between Scutari and today are eerie, from the politicians and bureaucrats demeaning and attacking the messenger, to the twisting of the numbers and manipulation of statistics. The fraud over the supplies. The refusal to follow her advice. She would feel right at home.

She would have a lot to say about how to deal with the coronavirus.

Please enable JavaScript to view the comments.